Background-mapping draws the wide and slender, the recognized and mysterious past to the current. All through my residency at the Aminah Robinson residence, I examined the impulses at the rear of my prose poem “Blood on a Blackberry” and discovered a kinship with the textile artist and author who created her home a artistic safe space. I crafted narratives by way of a blended media software of classic buttons, antique laces and materials, and textual content on cloth-like paper. The starting off position for “Blood on a Blackberry” and the crafting through this challenge was a photograph taken much more than a century ago that I identified in a household album. 3 generations of ancestral mothers held their bodies still exterior of what looked like a badly-designed cabin. What struck me was their gaze.

3 generations of women of all ages in Virginia. Photograph from the writer’s loved ones album. Museum artwork speak “Time and Reflection: Driving Her Gaze.”

What thoughts hid at the rear of their deep penetrating looks? Their bodies prompt a permanence in the Virginia landscape all around them. I knew the names of the ancestor mothers, but I realized minor of their life. What were being their tricks? What tracks did they sing? What wishes sat in their hearts? Stirred their hearts? What had been the night time appears and day sounds they heard? I desired to know their feelings about the earth all around them. What frightened them? How did they speak when sitting with good friends? What did they confess? How did they speak to strangers? What did they conceal? What was girlhood like? Womanhood? These issues led me to writing that explored how they must have felt.

Research was not enough to carry them to me. Recorded public record typically distorted or omitted the tales of these females, so my record-mapping relied on memories involved with thoughts. Toni Morrison termed memory “the deliberate act of remembering, a type of willed generation – to dwell on the way it appeared and why it appeared in a particular way.” The act of remembering through poetic language and collage assisted me to much better fully grasp these ancestor moms and give them their say.

Photos of the artist and visual texts of ancestor mothers hanging in studio at Aminah Robinson house.

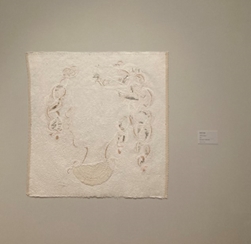

Working in Aminah Robinson’s studio, I traveled the line that carries my family members record and my inventive producing crossed new boundaries. The texts I made reimagined “Blood on a Blackberry” in hand-reduce shapes drawn from traditions of Black women’s stitchwork. As I lower excerpts from my prose and poetry in sheets of mulberry paper, I assembled fragmented reminiscences and reframed unrecorded history into visible narratives. Shade and texture marked childhood innocence, woman vulnerability, and bits of memories.

The blackberry in my storytelling became a metaphor for Black lifestyle manufactured from the poetry of my mother’s speech, a southern poetics as she recalled the ingredients of a recipe. As she reminisced about baking, I recalled weekends accumulating berries in patches alongside country roadways, the labor of kids collecting berries, inserting them in buckets, going for walks alongside roadways fearful of snakes, listening to what may be ahead or hidden in the bushes and bramble. Those people reminiscences of blackberry cobbler proposed the handwork, craftwork, and lovework Black families lean on to endure wrestle and celebrate lifetime.

In a museum converse on July 24, 2022, I linked my artistic encounters through the residency and shared how inquiries about ancestors infused my storytelling. The Blood on a Blackberry collection exhibited at the museum expressed the expansion of my crafting into multidisciplinary form. The levels of collage, silhouette, and stitched patterns in “Blood on a Blackberry,” “Blackberry Cobbler,” “Braids,” “Can’t See the Highway In advance,” “Sit Facet Me,” “Behind Her Gaze,” “Fannie,” “1870 Census,” and “1880 Census” confronted the past and imagined memories. The final panels in the show launched my tribute to Fannie, born in 1840, a likely enslaved foremother. Whilst her life time rooted my maternal line in Caroline County, Virginia, investigate exposed sparse lines of biography. I faced a lacking webpage in background.

Photograph of artist’s gallery discuss and dialogue of “Fannie,” “1870 Census,” and “1880 Census.”

Aminah Robinson comprehended the toil of reconstructing what she named the “missing webpages of American historical past.” Making use of stitchwork, drawing, and portray she re-membered the previous, preserved marginalized voices, and documented record. She marked historic times relating existence moments of the Black group she lived in and beloved. Her function talked again to the erasures of record. As a result, the home at 791 Sunbury Highway, its contents, and Robinson’s visual storytelling held specific meaning as I worked there.

I wrote “Sit Facet Me” during silent several hours of reflection. The times immediately after the incidents in “Blood on a Blackberry” required the grandmother and Sweet Boy or girl to sit and gather their toughness. The get started of their discussion came to me as poetry and collage. Their story has not ended there is much more to know and assert and visualize.

Photograph of artist reducing “Sit Aspect Me” in studio.

Photograph of “Sit Aspect Me” in the museum gallery. Graphic courtesy of Steve Harrison.

Sit Side Me

By Darlene Taylor

Tasting the purple-black spoon against a bowl mouth,

oven heat sweating sweet nutmeg black,

she halts her kitchen baking.

Sit facet me, she says.

I want to sit in her lap, my chin on her shoulder.

Her warm, dim eyes cloud. She leans ahead

near adequate that I can stick to her gaze.

There’s substantially to do, she claims,

positioning paper and pencil on the table.

Write this.

Somewhere out the window a hen whistles.

She catches its voice and styles the superior and low

into terms to reveal the wrongness and lostness

that took me from university. A girl was snatched.

She recall the ruined slip, torn guide pages,

and the flattened patch.

The words in my hands scratch.

The paper is too brief, and I can not create.

The thick bramble and thorns make my hands nonetheless.

She requires the memory and it belong to her.

Her eyes my eyes, her pores and skin my pores and skin.

She know the ache as it handed from me to her,

she know it like sin staining generations,

repeating, remembering, repeating, remembering.

Remembering like she know what it come to feel like to be a lady,

her fingers slide throughout the vinyl desk area to the paper.

Why quit producing? But I don’t answer.

And she don’t make me. Instead, she prospects me

down her memory of staying a girl.

When she was a girl, there was no faculty,

no publications, no letter creating.

Just thick patches of eco-friendly and dusty red clay road.

We consider to the only street. She appears to be like a great deal taller

with her hair braided in opposition to the sky.

Consider my hand, sweet child.

Collectively we make this wander, hold this aged road.

A milky sky flattens and eats steam. Clouds spittle and bend extensive the street.

Pictures of slash and collage on banners as they dangle in the studio at the Aminah Robinson dwelling.

Blood on a Blackberry

By Darlene Taylor

The street bends. In a position the place a lady was snatched, no one states her name. They converse about the

bloody slip, not the lost woman. The blacktop road curves there and drops. Just can’t see what’s in advance

so, I hear. Insects scratch their legs and wind their wings earlier mentioned their backs. The street sounds

secure.

Every day I stroll on your own on the schoolhouse street, trying to keep my eyes on where I’m likely,

not wherever I been. Bruises on my shoulder from carrying guides and notebooks, pencils and

crayons.

Pebbles crunch. An engine grinds, brakes screech. I move into a cloud of pink dust and weeds.

The sandy flavor of highway dust dries my tongue. Older boys, suggest boys, cursing beer-drunk boys

chortle and bluster—“Rusty Girl.” They travel rapid. Their laughs fade. Feathers of a bent bluebird impale the road. Sun beats the crushed chook.

Slicing through the tall, tall grass, I pick up a stick to warn. Songs and sticks have energy about

snakes. Bramble snaps. Wild berries squish underneath my feet. The ripe scent will make my tummy

grumble. Briar thorns prick my pores and skin, creating my fingertips bleed. Plucking handfuls, I try to eat.

Blood on a blackberry ruins the style.

Guides spill. Backwards I fall. Web pages tear. Lessons brown like sugar, cinnamon,

nutmeg. Blackberry stain. Thistles and nettles grate my legs and thighs. Coarse

laughter, not from within me. A boy, a laughing boy, a mean boy. Berry black stains my

gown. I operate. Home.

The solar burns as a result of kitchen home windows, warming, baking. I roll my purple-tipped fingers into

my palms.

Sweet child, grandmother will say. Wise woman.

Tomorrow. On the schoolhouse road.

Pictures of artist chopping textual content and discussing multidisciplinary crafting.