In 1940, William Dobell (1899-1970) returned to Australia after ten years in Europe. He completed The Cypriot (illustrated) that same year, a portrait of his friend Aegus Gabrielides. Was it the first major painting he produced, and what is the mystery behind the work?

RELATED: The life and art of William Dobell

DELVE DEEPER: The Cypriot

Dobell was renowned for his incisive portraits, and won the Archibald Prize for portraiture three times (1943, 1948 and 1959). He often embellished aspects of his sitter’s appearance in order to draw out their most distinctive traits. This is true of his portrait of Gabrielides, the young man who regards us with indifference.

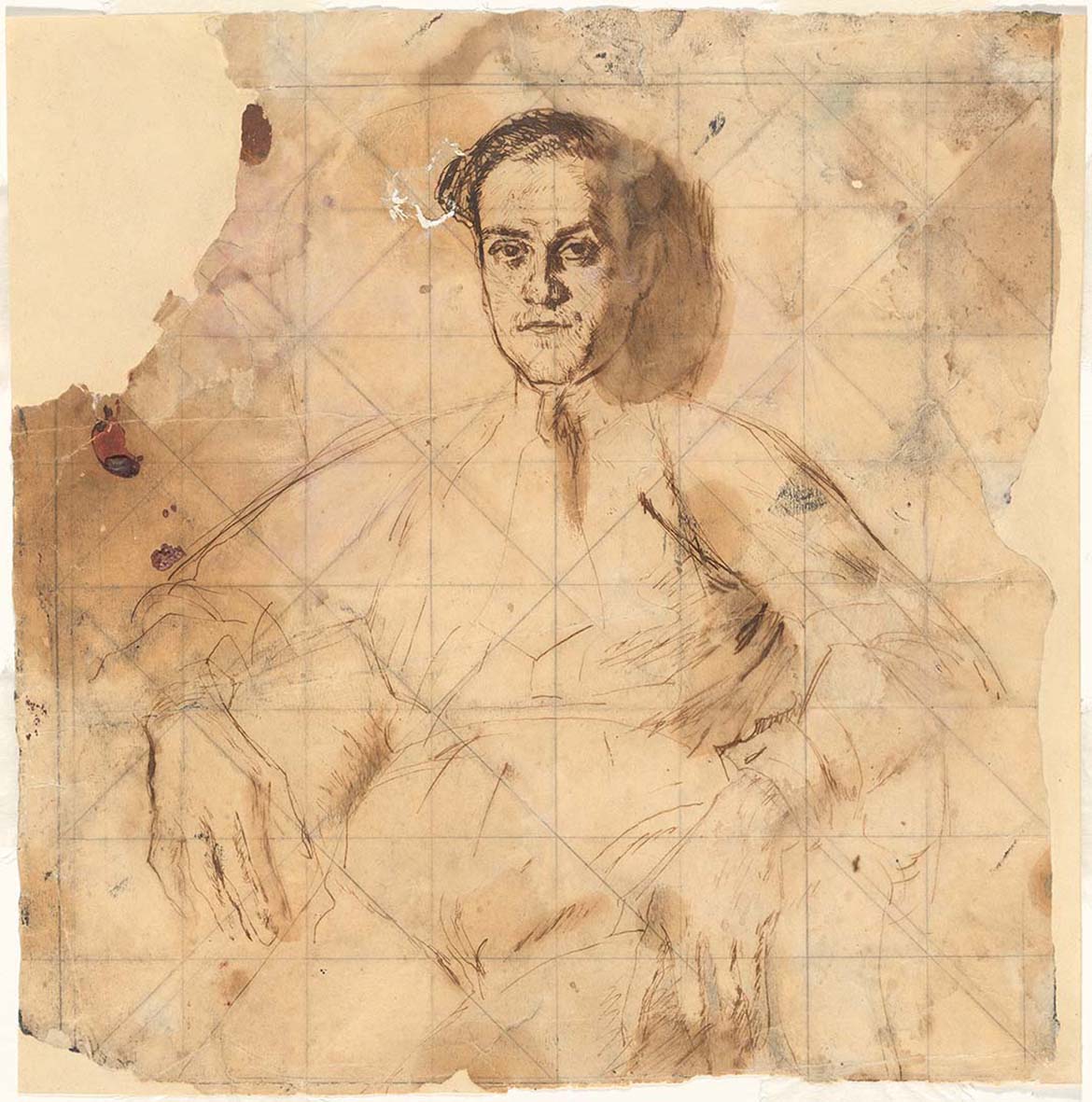

William Dobell ‘Study for the painting The Cypriot’

Gabrielides was a Greek waiter who worked in the London cafe frequented by Dobell in the 1930s. While Dobell’s early sketches portray an unassuming figure (illustrated), the finished painting presents a far more imposing character.

When painting a portrait, Dobell usually completed a series of pencil sketches in the sitter’s presence, seeking to capture key characteristics. He would then embark on a number of small studies in gouache or oil, each reflecting a different mood, then would paint the final version of the portrait based on these preliminary sketches, selecting the most insightful as a guide, but working neither directly from it, nor his model.

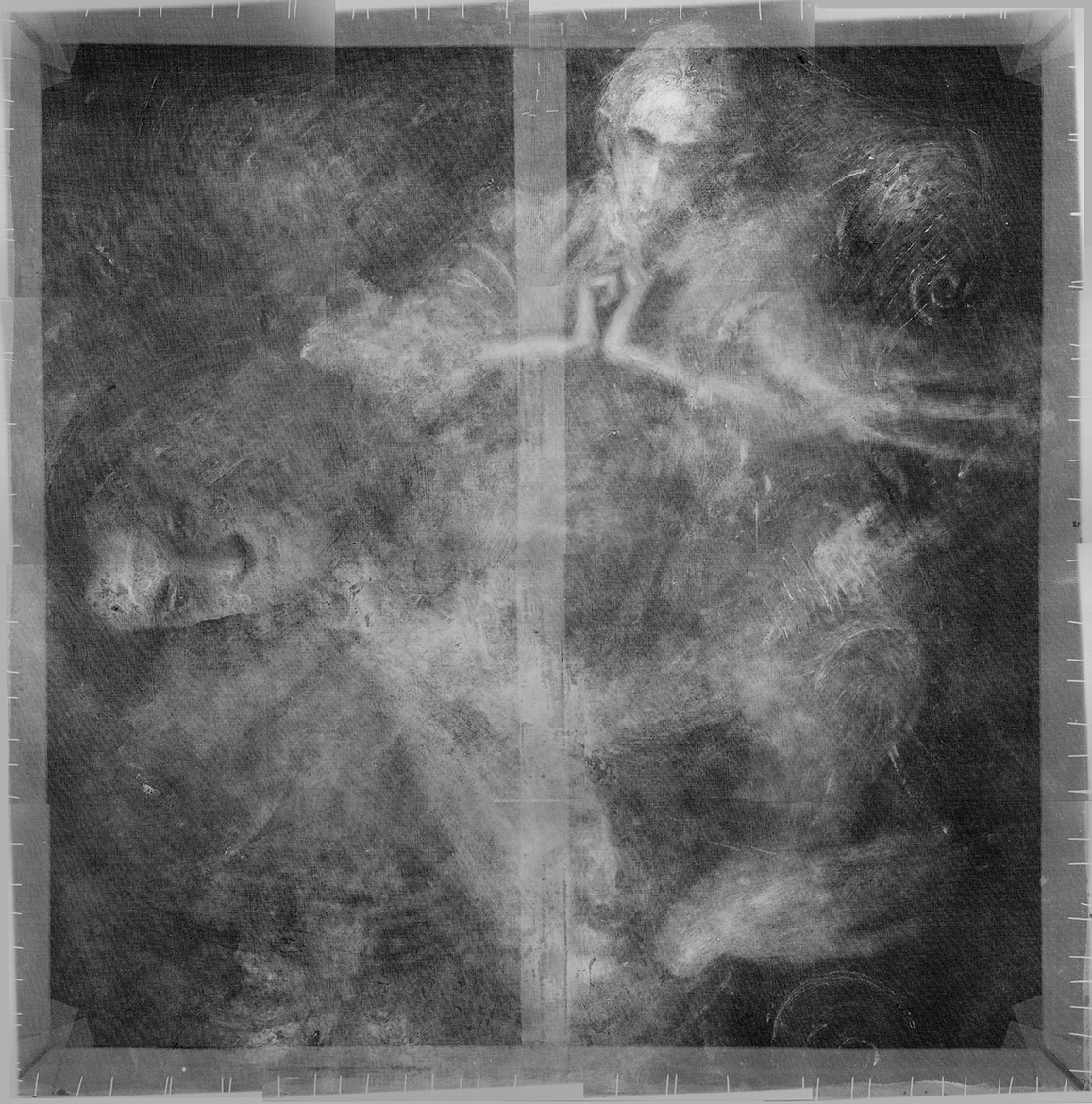

Look closely at the X-ray of the painting (illustrated). You can clearly distinguish the image of The Cypriot.

X-ray of ‘The Cypriot’

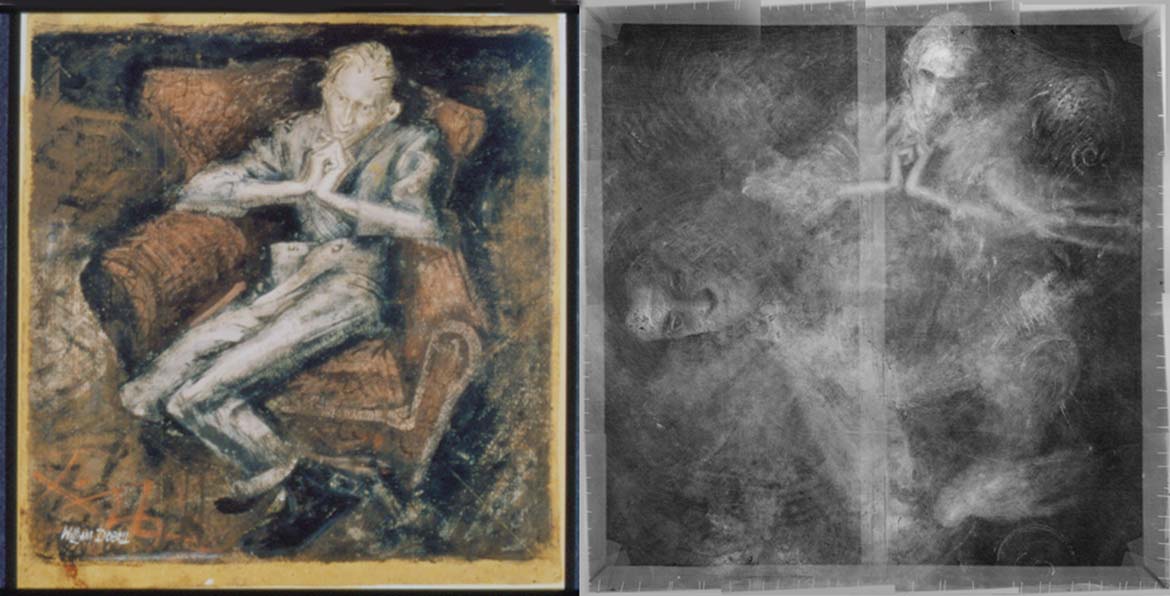

William Dobell ‘The Cypriot’

Now if we rotate the painting 90 degrees to the left, what this reveals is that there is another completed painting which lies underneath The Cypriot.

X-ray of ‘The Cypriot’ rotated showing under-painting

X-ray of ‘The Cypriot’ rotated

Now compare the X-ray with the small watercolour study from the Art Gallery of New South Wales called Boy lounging 1937. Clearly our X-ray also contains the ‘bones’ of Boy lounging which lies completed and unseen beneath The Cypriot.

‘Study for ‘Boy lounging‘ and X-ray of ‘The Cypriot’ showing under-painting

Why did Dobell paint over his initial painting?

Dobell was still poor, working with old brushes that had dried on the journey home to Australia. The abundance of brush hairs embedded in the painting’s surface are testimony to this. Chemical analysis of the paint layers show that he was using a combination of oil-based house paints and artist’s paints.

The artist’s economic situation, the large area of canvas to cover, as well as the scarcity of artist’s oil paints (owing to their requisition for use by official war artists during World War II) all contributed to a combination of paints being used. Economics might also account for Dobell’s re-use of the stretcher and canvas.

On his return, the publisher Sydney Ure Smith promoted Dobell as the ‘heir to George Lambert’ (1873-1930), and the artist felt compelled to produce his best work. But Boy lounging was not the ‘masterpiece’ the artist had aspired to produce on his return.

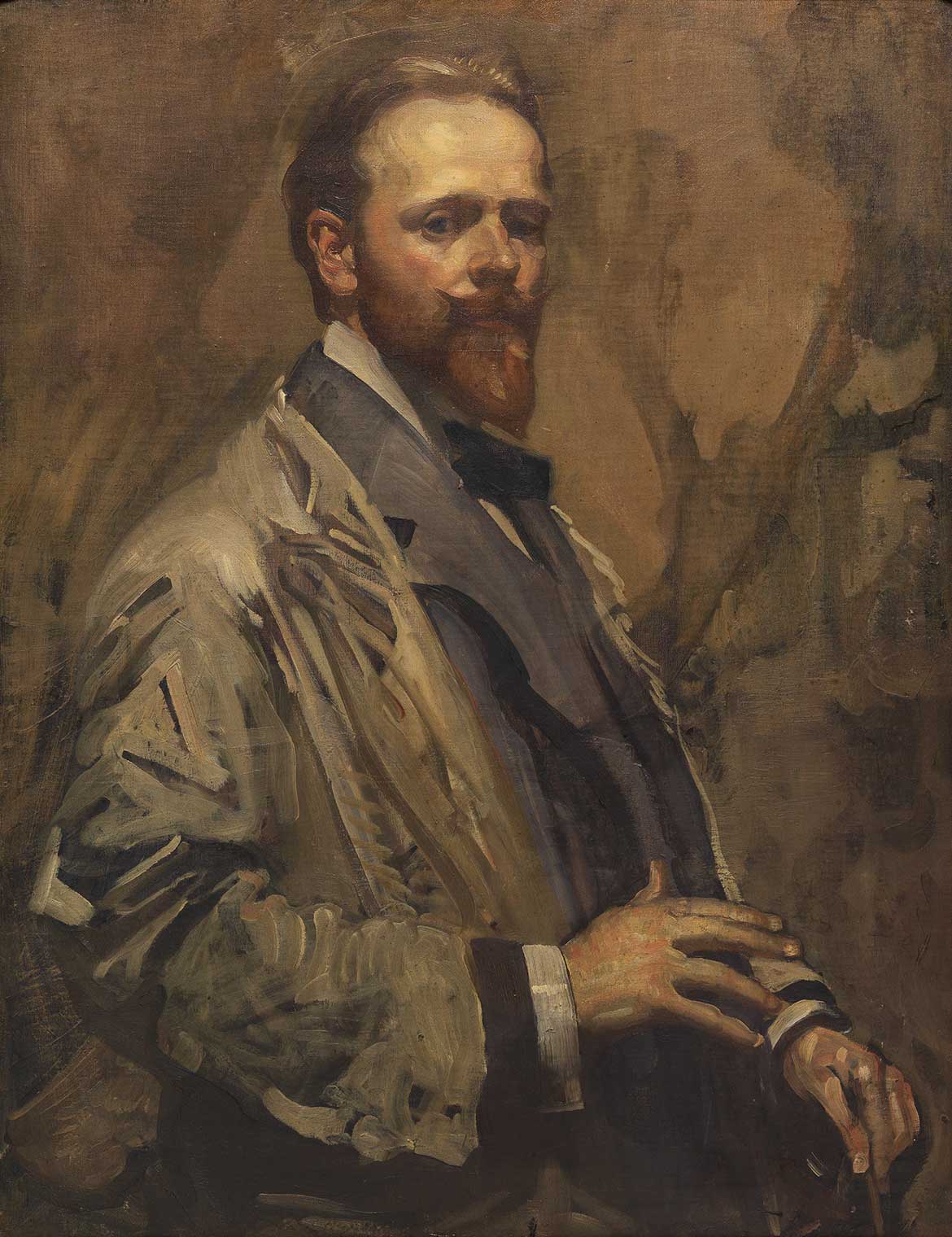

George W Lambert ‘Self portrait’

Unhappy with the finish of the painting, Dobell turned to the subject who had preoccupied him during his last six years in London. His many studies for The Cypriot stood him in good stead; he painted Gabrielides with great assurance and spirit. This is the artist at the peak of his painting technique. He draws inspiration from old master paintings he studied in Europe, such as Italian Mannerist painter Agnolo di Cosimo, usually known as Bronzino (illustrated).

Dobell’s mature style in The Cypriot reconciles the problems confronting a modernist painter who wanted to refer to classic masters and to contemporary, interior tensions.

Edited extracts sourced from John Hook, former Senior Conservator (Paintings), QAGOMA.

Agnolo di Cosimo ‘Portrait of Bartolomeo Panciatichi’

#QAGOMA